This page is rather long to scroll down, so if you only want to read about a specific topic then just click on the chapter heading below to access it:

- EL POCITO – a garden of our own again

- how it evolved (2009-2019)

- olives

- grapes

- making incense

- things i wish i’d got right from the beginning

- tea garden

EL POCITO – a garden of our own again

All 2.5 hectares of it (that’s about 6 acres), surrounded by 182,000 hectares of pines/ oak/ sweet chestnut/ apples/ vines, as well as many other kinds of tree. This whole region is mountainous, and the land at El Pocito was no exception, with at least a 100 metre drop from the top to the bottom, and contoured in a horseshoe shape, resembling an amphitheatre, so wherever you are it is possible to be heard and usually seen too. The house is tucked away at the top left-hand corner.

This land has had people living on it for a long time. There are prehistoric remains nearby, dry stone walls and terracing still remain, ancient olives, and in living memory has been used both as a pine plantation then an oak forest to fatten pigs (Jamon being the major local industry).

My first impression was that it had been terribly exploited. Nothing growing but a few oaks and a lot of dust. All but for one tiny part, which was quite lush, where there were wild figs/ grape/ rose/ and brambles. This, and the name (El Pocito translates as little well), giving us the confidence to go ahead with the purchase. Later we discovered plentiful water, close to the surface, and the main reason why it had looked so awful was the local habit of dehesa, which basically means brush-cutting everything to keep it looking clean.

The house is 600 metres above sea level and the surrounding area (in a NE direction) continues to rise, reaching about 900 m at its highest point. This has been very useful as it keeps out most of the colder/ stronger winds. The downside is it delays the appearance of the sun in high summer (especially when we want to use the solar panels). Either side of the house (SE & NW) the height remains the same, the neighbouring pine plantations offering shelter from wind. In front of the house (SW) the site drops steeply, with a river just beyond the bottom that flows most of the year. Wind from this direction is rare, but when it comes, either from the Canaries or N Africa, this usually means trouble. The view from the house is panoramic, 180 degrees which on a clear day allows you to see as far as the Portuguese border (60 km away), all of which is more or less uninhabited (by people).

The topsoil of the site is a form of sand, which I prefer, as this is really easy to work in the winter (the coolest time) but turning rock hard in the summer (when it is too hot to do much anyway). Underneath this are a wide variety of substratum, a mixture of crumbly orange rock/ granite/ and clay. When we arrived, the entire surface was also covered with millions of small rocks/ boulders. A nightmare to walk on, especially on the steepest parts, but has proved invaluable as raw material for building projects and creating swales/ terraces.

Climate here is glibly referred to as Mediterranean, which is both meaningless and misleading. El Pocito has a completely different microclimate to the nearby town of Almonaster la Real (a couple of hundred metres as the crow flies). The best description I can think of is Cornwall, but a lot hotter from June to October. Winter is certainly the same, with rarely any snow or frost, but cold. Spring is the most beautiful time. Summer is a sort of winter, nothing grows. Autumn is a second spring, when everything comes back to life.

Our plan from the very start was to plant/ grow a WYLDEWOOD, the ancient word for natural forest, and when that was established, fill the spaces with as many smaller trees/ shrubs/ perennials/ and wild annuals as possible. There was no specific design, which was intentional. By then I had been gardening for more than 30 years, and if I’d learnt anything it was that gardening is the planting of the wrong plants in the wrong place. If you want it work you have to do it intuitively, let nature tell you what it needs.

Eventually this would provide all our food/ fuel/ medicine/ plus whatever else we had needed to earn money. This is what Rudolf Steiner called the only sustainable way our species can exist. Where we take only from nature what it offers to harvest, nothing else should be touched/ exported/ or imported. At the same time giving the same respect for all other species.

I deliberately choose wyldewood, instead of the better-known forest garden, to describe what we do. Because firstly I do not want to be associated with permaculture, the ism that first coined the phrase, and is not about helping save the planet but a thinly veiled pyramid scheme for making its followers a lot of money. Tinkering away in back gardens, allotments, or even large tracts of land (rewilding), while still living conventionally, spending money, is not going to help anyone. Wyldewood on the other hand simply means living in a way that benefits nature.

I also wanted to get away from what most people today perceive as a forest or forestry, which is in no way sustainable, simply blatant destructiveness. The difference is easy to spot. Plantations, where almost everything is planted uniformly, usually with just one or two species, and a scary absence of anything else growing/ living within them, is where the trees are chosen to crop in the shortest possible time and with the least need for inputs. These “forests” simply exist so the owners can make a quick profit and we can have yet more pointless products from IKEA, equally unnecessary and unwanted packaging, and provide poor quality overpriced fuel for pellet stoves and power stations. All of which is killing the planet, but permitted because vested interest, those who rule over us and have been making the lives of the majority a misery throughout history, hold all the power. Hoodwinking the gullible and stupid, with reassuring labels such as renewable resource (which couldn’t be further from the truth) and certified (conservation grade/ organic/ bio-dynamic/ agroforestry/ commercial forest gardening/ or whatever other scam that has since been invented). Whatever their claims it’s simply about making money, a lot of it, as quickly as possible. Nothing natural or of benefit to Nature.

Wyldewoods are also a permanent resource. Not for cutting down/ replanting, but allowed to exist un-managed for eternity, providing a safe habitat for a vast array of other interdependent species.

They are our only hope too, if we want to survive extinction. Save the eco-system/ biodiversity, the invisible organism that works ceaselessly to create everything, providing us with enough clean air to breathe, healthy food to sustain our bodies, pure water to re-energise with. Because it is on the verge of imminent collapse.

10,000 years ago, there wasn’t a problem. There were only 300 million of us then, as opposed to the 7 billion now. A time when we still had a place in the grand scheme of things. Concepts like poverty had yet to be invented. The need for any kind of infrastructure/ planning/ or other kind of organisation had not even been considered. No-one needed to supervise anyone or anything. There was no dividing up of land, no ownership, no homes/ tools/ language/ gods/ or money. And no-one even spent a single second of their life in labour, certainly never for someone else. That is, until someone somewhere came up with the idea of imposing their pinhead logic on everything, no doubt because they wanted to be different, more powerful, and from that moment that idea infected the species and spread, unchecked, exponentially, until what we are left with that matters is a very little. Life as we know it is about to end, unless we wake up and stop this craziness.

A wyldewood is therefore not about making a garden but changing everything about the way we live. From realising how much we actually need to earn and spend, to replanting every bit of the planet to help the ecology function properly again. Which sounds awfully hard, the responsibility of governments not individuals, but that’s just our egos talking. Anyone can make all the necessary changes in a blink of the eye, it just takes a commitment and responsibility, a desire to survive. Even living on a lot less (or no) money is easy and doesn’t have to change a thing about the quality of your life (check out the living on less money page). You don’t even have to wait for someone else to start, because that isn’t going to happen, vested interest really doesn’t care about the future, they won’t live to see it, or they have already made their own provision for when the shit hits the fan. No, you can do this by and for yourself. There’s nothing to join, no membership to pay, no courses to attend, no textbooks or magazines to buy, read or digest, no certificates to give you the validation, no hierarchy to ascend. And it isn’t even necessary to have a lot of land. The only requirement is to grasp and apply the two underlying principles. Spend as little as possible (or nothing), and plant as much as you can, especially permanent edible plants. If you still need some inspiration, then read THE MAN WHO PLANTED TREES by Jean Giono. To make this even easier, here’s a quick step-by-step guide:

Just think about the place where you want to plant and imagine it as a three-dimensional world made up of seven different vertical layers. (1) being the tallest and widest trees, these are spaced so they’ll leave enough room in-between for the next layer. (2) mid-sized trees and large shrubs. Between these go (3) ordinary-sized shrubs. Followed by (4) perennials and self-seeding annuals. Underneath which are the (5) ground cover plants, and (6) root plants. The remaining layer (7) is climbing plants. You can use my (click to download) plant list to help you choose or get a copy of Ken Fern’s book PLANTS FOR A FUTURE (ISBN 1-85623-011-2). He’s another luminary of mine, the driving force behind the PLANTS FOR A FUTURE project in Cornwall and has produced the most comprehensive and easy to understand public access database on the subject yet, available online at http://www.pfaf.org/ for free searches, or even better as a download/ CD to use at home.

*

how it evolved (2009-2019)

swipe to see more photos

During our first summer very little got done, there were just too many other more pressing things to attend to, the heat was a problem, and the sheer scale of six acres meant we couldn’t even decide where to start. By winter only having managed to plant about fifty fruit trees, bought at a market in nearby Portugal, all of which promptly got eaten by deer. My knee-jerk reaction then was to erect a fence. Luckily, we had hardly any money so it could only cover a small area, about one acre. The most obvious place being to put it around the house. Not the best land, in fact the very worst, but from previous experience I knew it was important to keep the journeying back and forth down to a minimum, especially on a steeply sloping site. The one good thing to come out of this was it got us focussed. Work began in earnest, with me creating terraces (everything is a lot easier on the flat, also helps with soil erosion), and Maureen organised the vegetable plot.

By the next summer (2010) we’d learnt a lot about our new environment. Like it lacked virtually all the conditions needed for growing any kind of veg. That trees b(r)ought in, even when fenced, don’t thrive, they cannot adapt to a wild existence. Which prompted another time and money wasting mistake, installing an irrigation system (described later). Our plan to grow our food was put on hold, until trees could provide sufficient shade and fertility. I concentrated on the terracing, all done by hand (using a pickaxe) and growing trees from seeds.

The following spring (2011) we got a hive of bees (also described later). And by the summer felt finally acclimatised to the heat. Work began on a pond for grey water treatment. The previous owner had dug one using a JCB, but with vertical sides and during torrential rain these collapsed, filling it in. I excavated it again, this time terraced, then planted trees and reeds to hold it all together. One of the trees there is now 5 m high.

During 2013 Maureen’s cancer took over everything and work on the garden came to a halt. Then she died, and it was hard enough to barely function, so by the end of 2015, the sixth year, progress had slowed dramatically. 95% of the fenced-in area had been roughly terraced, but then I discovered they needed to slope backwards to retain the rainfall. That winter more was finished. By then there were about 500 new trees planted (all from seed), with a 2 metre space between for shrubs to go in later.

Then came the summer of 2016, which was the hottest here ever. I wasn’t using the irrigation system anymore and a huge number of the trees died. Or so I thought, for most had shed their leaves very early on. Some subsequently recovered the following year. Others were replaced with remaining nursery stock, and the rest with grafts, using the apple/ loquat/ citrus, which weren’t affected, I guess because their roots have found the natural water table.

In 2017 all the terracing work within the internal fenced-off area was finally finished.

The rest, the other five acres, has been worked on too. In March 2015 a new law came into effect in Spain which meant I was obliged to create a clean firebreak around the entire perimeter of the land or face a massive fine/ imprisonment. As I no longer wanted to use any petrol-driven devices on the land this has all been done by hand. No mean feat, on top of everything else, but with merely a handsaw and long-handled shears to start with, then just secateurs, only an hour a day. Which in turn created not only a lot of useful brushwood for the stove, but thanks to my ancient copy of ANOTHER KIND OF GARDEN, by Ida & Jean Pain, who had a similar garden (though slightly bigger at 241 hectares, in Provence in the 1970s), compost too.

2017 also marked a huge change in the land. From what had been such a dead looking place when we first moved in, now all was green and lush. With no inputs or irrigation. The areas left to regenerate naturally, outside the fence, seeing the best recovery, with literally thousands of new trees and shrubs reappearing (probably after being dormant for decades), despite the wild boar and deer. Nature really does know best!

Another discovery was the importance of shade plants, especially getting them established first. Instead, I had concentrated on growing and planting trees, thinking their canopies would do that job, wasting many valuable planting years. Thinking too that irrigating was the answer, only to realise that unless it was on 24/7 99% simply evaporates. Mulching proved pointless as well, far too much to cover, a very steep slope, and strong winds. So, it did have to be done by planting, but with what? That’s when I started to look at what was there already, realise that nature knows best, in this case gorse. While adding plants that seemed to survive without any help, English lavender and rosemary. Rosemary being especially easy to propagate infinitely from cuttings. One autumn I simply trimmed some plants and stuck the tops into a wild patch of ground and 200 new plants were created.

My most startling discovery was the right way to plant trees. I thought I knew, especially having grown from seed at least 5000 trees just here, and who knows in all the other gardens I’ve worked on. But only a tiny proportion of those actually survived long-term. Now I know why. Not a lack of irrigation or wrong species (I only grew what was there already), but that the roots couldn’t get down to the natural water-table fast enough, penetrate the bedrock that lies close to the sandy surface. What I should have done therefore (what a wonderful/ irritating thing hindsight is) was drill a one metre hole for each. Either by auger/ post borer, or if that doesn’t work a cordless SDS drill with 25mm masonry bit.

The summer of 2018 was the mildest in the eighteen years I’d been in Iberia, more like spring never ended, simply went straight to autumn (which is like another spring here), missing out summer. We had the wettest (and mildest) February to July for decades, with the first real hot day not arriving until the 17th of July. No-one can remember it being like that, at least not since the 1950s. And it was seemingly at odds with climate change too. The region, the Sierra de Aracena, seems to be the only place in Europe not to have increased in temperature. Very odd, but the plants/ wildlife/ and residents are not complaining. Everywhere is so lush and green. And at El Pocito in particular there are now wild herbs and other annuals previously not seen before. Even the trees I thought were long dead have put up new shoots. And for the first time the vine plants had tiny fruit.

Christmas 2018. Autumn that year was the wettest for a long time. Incredible to see so much green, and plants still growing. It remained mild too, sufficient to have the door and windows of the house open all day and only light the wood stove later in the evening. But the most spectacular thing was the mushroom harvest. Usually this goes on for about a month, this time it was almost three, and there were so many (both types and quantity) that it was only necessary to search within a 20 metre radius of the house for enough to eat. Sweet chestnuts were plentiful also, and the pine nut harvest was just as good too.

I finally managed to get an auger, albeit the manual kind (no way to power a SDS drill at El Pocito), and started to plant the trees raised from seed. It was a bit late, which was a worry because I like to get all this kind of work (tree planting/ transplanting) done in November, so the roots have time to grow before the summer, but there were so many waiting it was fairer to take the risk than suffer the stress of another year in pots. Well, an auger is hard work, especially if you hit a stone. The first hole I made was a cinch, all done in a couple of minutes. The second hit rock. Started again a little further away, hit rock again. Eventually it ended up taking three hours. The third hit clay, which I hate, nearly giving me a hernia trying to lift the thing out each time. Got them all in though. What was interesting, was there was always soil left over. Then when it rained the plant/ hole dropped by that amount leaving a depression which allowed more rainwater to collect and provided a bit of shade.

What might be a unique event happened in February (2019). One of the lemon trees, planted in 2010, produced oranges. Apparently, this is impossible, even though the rootstock is probably a wild orange, it has to be either from a shoot below the graft, or the graft has to die, neither of which was the case. Every year up ‘til then it had been only lemons. Though good news in one way, because none of the twenty or so orange trees I planted that same year had fruited yet.

March 2019. All the trees transplanted with the new “auger method” survived and are in leaf. Same success with the grafting. But best news of all is the arrival of a new visitor, an otter, seen here in this video just 5m from the house. Why here, is a complete mystery, there are small rivers nearby but nothing to have sufficient fish, perhaps this one is a vegan, like Woolly our black & white cat, who loves fruit.

Postscript on the “otter” sighting. Apparently, it is a mongoose. Well, whatever, impresses me. One more creature living in El Pocito.

*

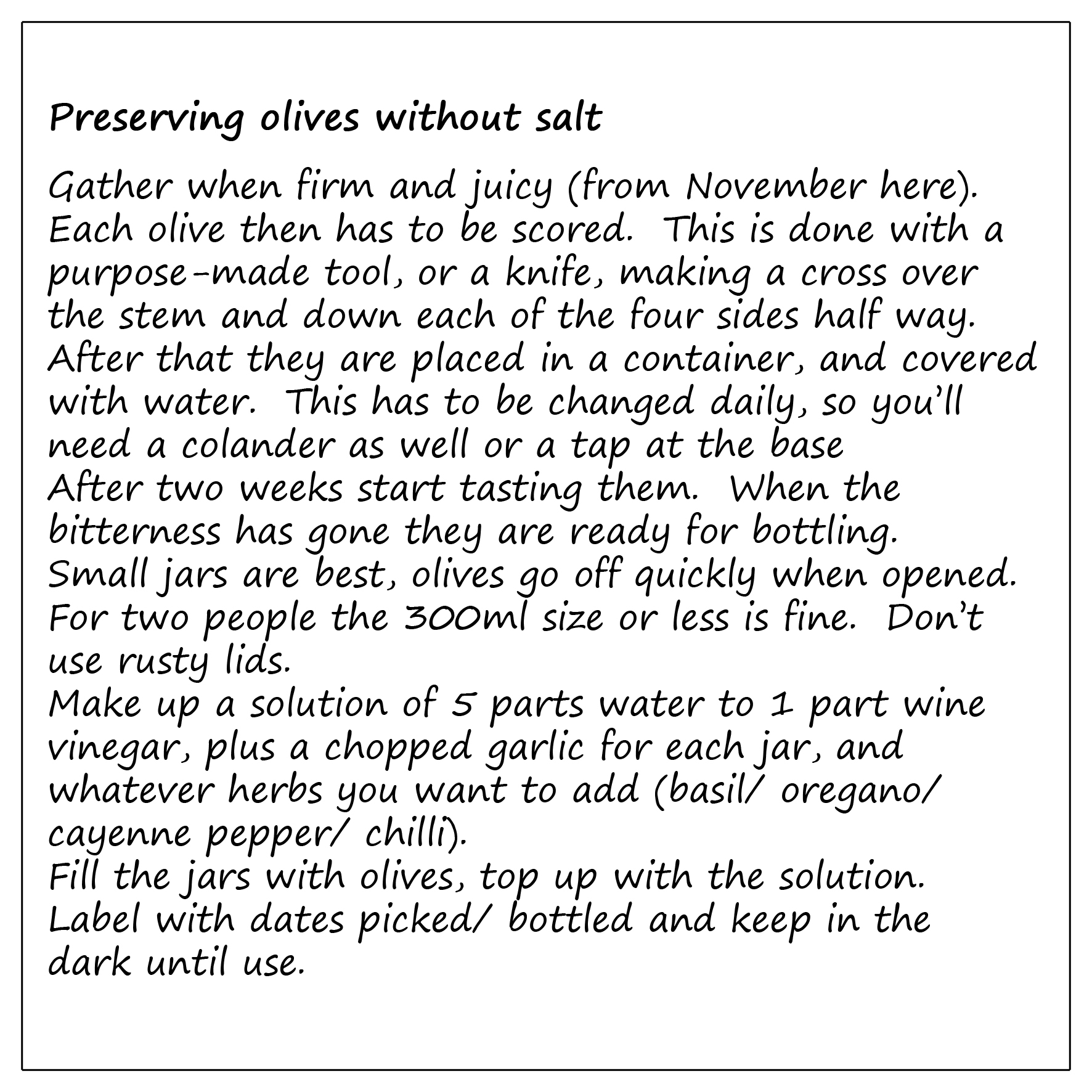

olives

Of specific interest at El Pocito are its olives, which are a particularly old/ hardy/ and vigorous variety. At first, I reckoned there were about a hundred (only some of which would fruit in any year), but now it’s obvious are a lot more, and as well as full-size trees there are literally hundreds coming up as suckers from what I presume were trees cut down in the past. Trimming just a few of the big ones has already created enough firewood to last us a whole winter (it is the best fuel for a wood-burner, pine being too greedy and oak too slow). The fruit we are able to collect is more than enough for eating/ preserving, and if we had a small olive press (the next project) we’d be self-sufficient in oil too (1 ltr requires 6 kgs of olives).

*

grapes

I also planted vines (or to be totally accurate, vine cuttings) with the aim of making our own wine, after a very dear friend in Galicia, one of the first organic growers there, sent us some from his finca, to get us started. Red for wine, and white for eating. This was in January 2011. Sadly, even though they were all heeled in immediately they must have dehydrated en-route because most eventually died, so the following December we went in search of replacements. This time in nearby Portugal, where our neighbour when we lived there, had started planting vines at the ripe old age of 72. He bought 40 plants from the Douro region and then took cuttings from those. By the time he was 83 he had 700 plants, taking up about an acre. His processing plant is a tiny shed, inside which is a large stainless steel, from which he manages to produce around 2000 litres of the most palatable wine I’ve ever tasted. The cuttings we brought back survived the driest winter on record and now there are about 40 plants.

*

making incense

Another idea we’ve had is making incense/ charcoal/ perfume. The Moors (when they occupied this area) planted cistus ladanifer for this purpose and El Pocito has plenty.

*

things i wish i’d got right from the beginning

We should have planted fig trees in front of the house. I saw them growing in Monchique, Portugal, and they gave the perfect shade in summer, as well as cooled/ moistened the surrounding air, plus gave off the most wonderful fragrance.

Saved all the seeds from the locally sourced fruit we eat. They germinate and grow much better than bought seed.

Stop trying to make the garden look neat and tidy. Chaos is how stuff survives in the real world; all plants have a purpose in the diverse sustainable scheme of things.

Install a massive polytunnel frame with shade cover, because trees in pots do not cope well with the heat of summer, and some essentials like comfrey/ nettles/ and mints (+ many important herb annuals) need constant shade/ water all year round.

*

tea garden

swipe to see more photos

Directly around the house are beds devoted solely to the herbs we use for making tea, from the fresh (not dried) leaves and flowers. The current list of plants we are using (in the entire garden) is:

agrimony, avocado, blackberry, catnip, chamomile, chrysanthemum, cistus, cleavers, comfrey, echinacea, evening primrose, fennel, giant hyssop, gorse, grape, guava, hawthorn, heather, hemp agrimony, honeysuckle, hyssop, jasmine, lavender, lemon balm, lemon geranium, lemon grass, lemon verbena, lime, liquorice, mallow, marigold, mexican tea, milk thistle, mint(s), mountain grape, nasturtium, nettle, olive, orange, passion fruit, peach, pennyroyal, perilla, pine needles, plantain, portuguese green tea, raspberry, rosa rugosa, rosemary, rue, sage, self-heal, st john’s wort, strawberry tree, spanish tea, stevia, wild carrot, willow, wild strawberry, wormwood, yarrow.

*